TEOTIHUACAN

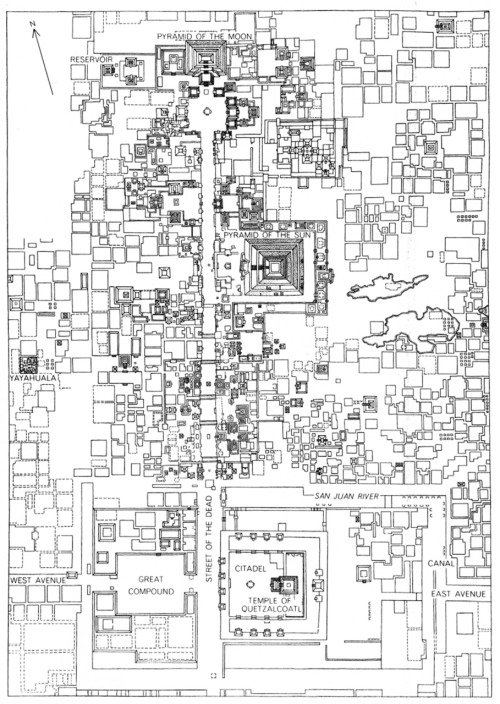

The pyramids at Teotihuacán.

Month by month, I circled in to frame the story in theoretical terms. And that was only the beginning.

A novel is made of details. Every character, on every page, has to be immersed in a perfectly visualized scene: using transportation, cooking, listening to radio programs, speaking in the particular jargon of an era. Wearing clothes. (Unless they aren’t, but that can’t last long.) Each detail has to be historically exact, and in this case “the era” involved dozens of different locations in two countries, crossing nearly thirty years.

I traveled to all the settings, on both sides of the border: Washington, D.C., Asheville, North Carolina, the Blue Ridge Parkway, on this side. On the other, I hiked through Mexican coastal jungles, hung out in villages, went to see a brujo, visited Mexico City’s archaeological and art museums, the preserved homes of Rivera and Kahlo and the Trotskys, and their personal archives.

I climbed the pyramids at Teotihuacán.

I’ve spent a lot of time in Mexico over the past thirty years, living near the border in Arizona for most of that time, so I drew on the past too, digging out old notebooks from assignments in the Yucatan and elsewhere. I only set scenes in places where I’ve been myself. When I create a world for the reader, I want to do it right, using all my senses.

That was the fun part, the “writer’s life” they show you in the movies. Here’s what they don’t show: the writer sitting in a chair in her study, glasses on her nose, coffee cup in hand, reading. For years and years. Biographies, court transcripts, political analyses from every angle, catalogues of women’s clothing from the ‘30’s and 40’s, recipe books, you name it. Everything ever written by or about Trotsky, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, J. Edgar Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, I tried to lay eyes on. I read literally thousands of newspaper and magazine articles documenting everyday life in the U.S. during World War II, and everything leading up to the post-war political freeze-up. Autobiographies of blacklisted artists. The internet was useful, many newspapers now have electronic archives, but mostly it served to lead me toward better things that are not online. I had to get my nose into a lot of dusty places. I pored over old letters and photo collections. I visited an old-car museum. This is a good example of the importance of primary sources: “Googling” a 1930’s Roadster won’t tell you how it feels to shift its gears, or that the windshield wiper is hand-operated by a lever over your head. Who would have thought? I loved the surprises. I learned that contrary to popular belief, the continental U.S. was attacked during WWII. The New York Times ran photos of the aftermath. The Japanese sent a submarine up the Columbia River and deployed a floatplane bomber, with the goal of setting the Oregon forests on fire and creating panic in the land. But the plan was rained out. History hinges on things like this, events that get forgotten – this is the soul of the story I wanted to tell. It was thrilling to immerse myself so deeply in the era. I dreamt of cooking breakfast for Trotsky, and became a curiosity for elderly men at dinner parties who quizzed me about arcane World War II trivia. The stacks of research materials grew tall in my office, like a forest of wobbly trees. I’ve cleared it all out now, making way for the next.

-

, on writing

The Lacuna.