BARRAGAN

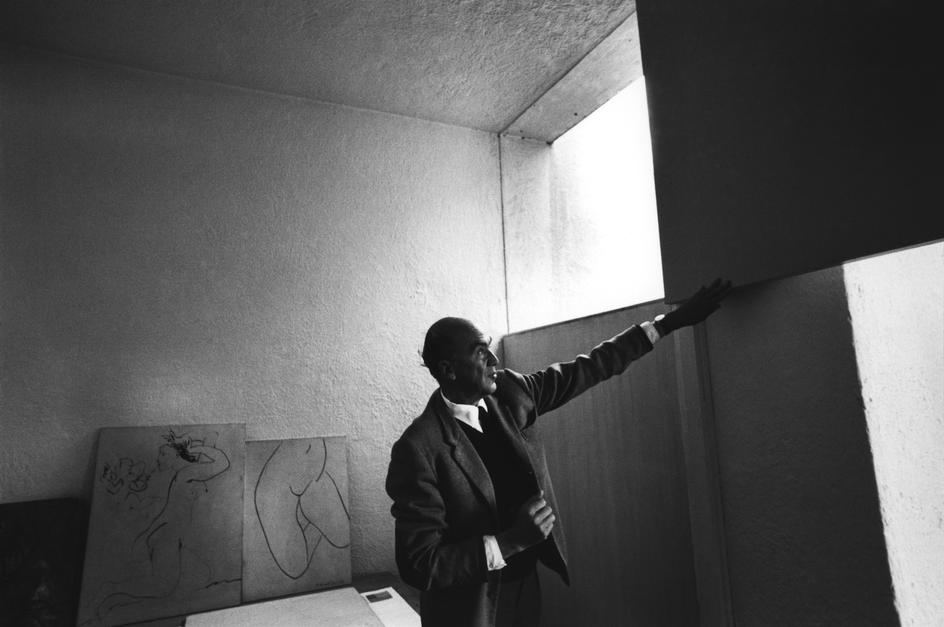

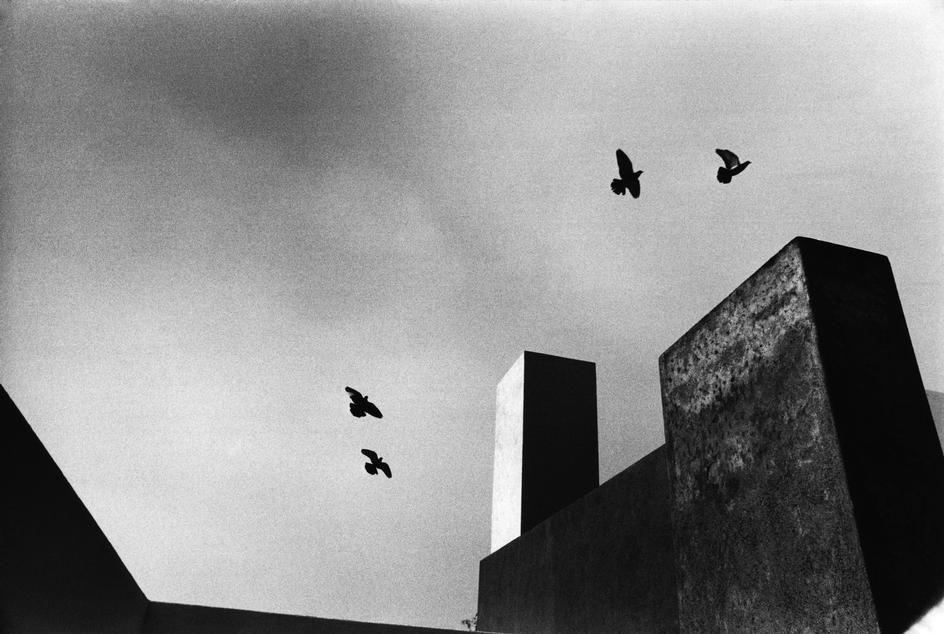

To see Barragan in black and white and grey is strange, knowing the intensity of colour in his work. The textures heightened, the images pulse with promise; as if about to erupt in all their fleshy pinkness.

To see Barragan in black and white and grey is strange, knowing the intensity of colour in his work. The textures heightened, the images pulse with promise; as if about to erupt in all their fleshy pinkness.

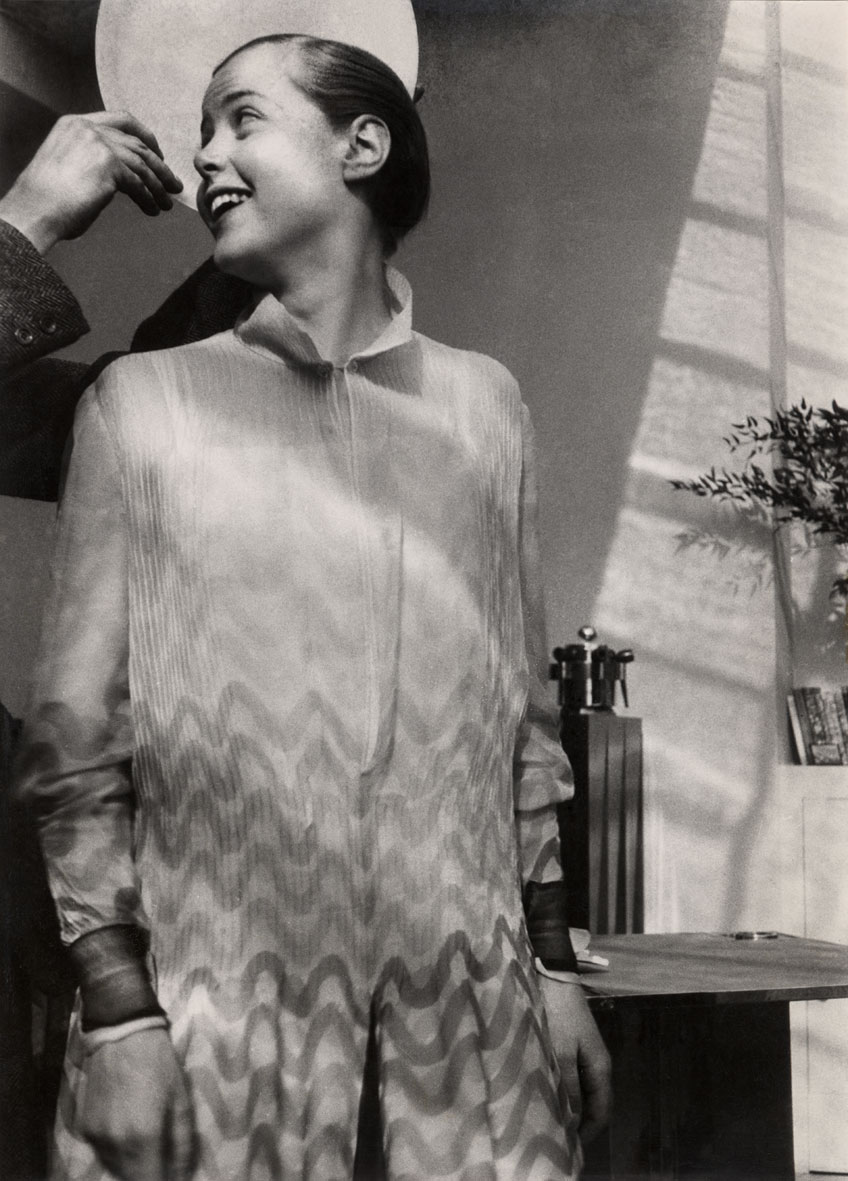

Charlotte Perriand in her studio in Montparnasse, ca. 1934.

Photo: Pierre Jeanneret, © 2010, ProLitteris, Zurich.

“The extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living.”

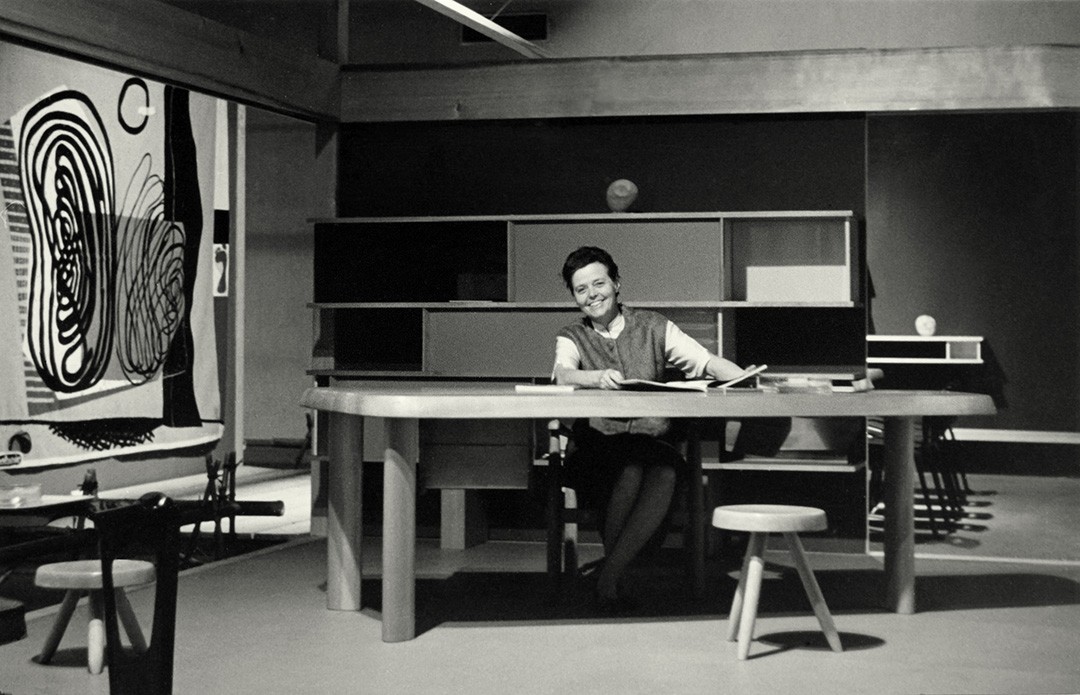

There aren't many people who seem better placed to discuss an art of living than Charlotte Perriand, whose life of 96 years had such breadth, impact and inspiration that it manages to continue to sing even now, 15 years after its end.

It is somewhat of a frustration, then, that not only her work, but her character are continually positioned alongside the demanding and prestigious Le Corbusier. For me, Charlotte is more than an adjacency to Corb, or a 'woman designer'. She is a muse: a strong mind with an immense sense of self, a body with which she engages in rich experiences of the world, a soul with an uninhibited capacity for creative production. Historian Mary McLeod takes up Perriand's case in her stellar essay Perriand: Reflections of feminism and modern architecture, published in the Harvard Design Magazine (2004), where she calls for histories of modern architecture, such as those that include Perriand, to look beyond reductive comparisons, and to seek to understand the richness and complexities of how gender is constructed and challenged through design practices.

Charlotte Perriand was woman of boundless design fluency, she was a master of translation, tirelessly working to transform her experiences of the world, through design, into visions of contemporary living. Architect, artist, traveler, designer, and urban planner, Perriand moved across scales, using her travel photography as a form of designerly-research, informing her projects. Her curiosity in the world around her seems to have been not only insatiable but also very precise: the cropping of her images revealing not only what she saw, but how she saw it.

Looking at Jeanneret's portrait of Perriand, above, I find myself looking with her, having first taken in her bare shoulders, the pearls, the way she has scooped her hair from her neck. Together we look beyond the flowers, beyond the deep reveals of the window, towards what in the blur we can only imagine is some kind of horizon. If there is an art of living it must start, I think, with an art of seeing, which, in turn, is linked with an almost unnerving intimacy to an art of being. I like to think that these are secrets that Charlotte knew too, and that they gave her a power to transcend the reductive assumptions of gender, and to quietly get on with what was important to her in making a life.

Perriand in her Studio

Frank Stella, New York, 1959 - Hollis Frampton

My first introduction to post-painterly abstract artist Frank Stella was when I was about 9 or 10. As part of one of those classic and formative childhood school projects, we were asked to research an artist and then to produce work 'in-the-style-of'. I can't remember why, or how I came across his work in that pre-internet era, but I chose Frank Stella.

There were paintings with titles like 'Zambesi', jarring colours, and minimalist geometries which folded over one another, turning the page into a three-dimensional surface. I thought it was wildly exciting. Until this stage in life, my favourite artist had been Claude Monet - so Stella was a revelation.

Now, my favourite Stella works are all about the parallel lines, in particular those making the shift from the precise and colourful to the imprecise and tonal. In these large-scale works, Stella imparts a depth to the space between the lines, which in turn gives the lines a quality of hovering, or buzzing in space. The lines are journeying tail-lights, rays conceived by squinting at the stars, or the strangely orderly formations on the inside of my eyelids. Whatever they are, in these works Stella masterfully moves us from the minimal to the spatial - a transition with architectural overtones.

This October, the Whitney will present the most comprehensive retrospective of his work yet. If only I could get there.

Ileana Sonnabend, 1963

Private collection

Zembesi, 1959.

Sometimes, in the evenings, I find it hard not to get lost in The Paris Review - and even harder to find my way back out of the Interviews. There's something about the rich reality of these characters, many of whom have spent years envisaging other characters, which is just so affirming.

This evening, I have been lounging about with Margaret Drabble. I can't say that I've ever read one of her novels - although I have quickly added some of her classics to my reading list. Towards the end of the interview, she refers to Freud a few times. She's grappling with events, with how the passing of time relates to who you are, and to where you are.

On surprises and familiarities (and a beautiful understanding of mortality):

There's an essay by Freud in which he discusses the uncanny feeling of being both familiar with and utterly surprised by something. I think this is one of the most distressing, but important feelings in life. The feeling that I knew this all along, but I never knew it before. Freud would argue we feel this about sex. The first time we find out what it actually is, we think “how absolutely astonishing and impossible,” but at the same time we know we knew.

I'm sure death feels a bit like that. In fact I've often had a dream in which I am just about to die and my last words are, “Oh, that was what it was like. I did know really, but now I know for real.” And then I wake up.

And on coincidence:

Freud takes a harsher view. His view is that they are coincidences and the idea that our need to see them as not being so, like our need to avoid that death really is death, contorts the whole of human life: that the whole of human culture is distorted by our desperate need to avoid the truth.

I'm perpetually tossed between these two interpretations of life. It is a fact that if you have faith of a certain sort, then certain things will happen for you or for those that you love. But this is only in a way like watering a plant. One of the images I like best is the plant in The Waterfall that Jane keeps on watering long after she thinks that it's dead. And then it begins to grow again.

Thinking about the new year, and how you want your life to play out. Obrist's rituals is a beautiful way of reconsidering how your everyday routines, which could become mundane, can be sculpted to provide a meaningful, and highly personal, backdrop to your life.

“Huxtable never let her readers, or anyone else who would listen, forget that architecture is not like the other arts. Paintings or dance performances you choose to see or not see, but architecture envelops us all. Everyone sees and experiences it. Huxtable insisted both that architecture is an art and that it is an art that everybody deserves to enjoy precisely because it constitutes the life of our inhabited places.”

Because crafting is living.

In 1990, a stoke robbed Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer of the movement of his right side, and most of his speech. Passing into this new phase of his life, Tranströmer continued to write poems capturing the rhythm of the Swedish seasons, the atmospheres of nature, and the passages of grief. In 2011, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his work, which is praised for its accessibility.

A magnificent pianist, since his stroke, many composers have produced left-hand only pieces specifically for Tomas to enjoy. He plays often, and listens often, seeing the music as a way to regain joy and hope in his life. The support he receives in life and in work, from his relationship with his wife Monica, is quite beautiful. Always a quite, supportive guide, since Tomas' stroke Monica has become a key part of the writing and reading process, such that the newer poems are guided by both their hands.

Knowing what it means to be himself - to write, to read, to enjoy music - is a testament to Tomas' fortitude of character. Doing the things which make you feel like you - however difficult they might become - defines your life with such beautiful clarify.

Tomas Tranströmer from Neil Astley on Vimeo.

Tomas Tranströmer from Neil Astley on Vimeo