FRANK STELLA

Frank Stella, New York, 1959 - Hollis Frampton

My first introduction to post-painterly abstract artist Frank Stella was when I was about 9 or 10. As part of one of those classic and formative childhood school projects, we were asked to research an artist and then to produce work 'in-the-style-of'. I can't remember why, or how I came across his work in that pre-internet era, but I chose Frank Stella.

There were paintings with titles like 'Zambesi', jarring colours, and minimalist geometries which folded over one another, turning the page into a three-dimensional surface. I thought it was wildly exciting. Until this stage in life, my favourite artist had been Claude Monet - so Stella was a revelation.

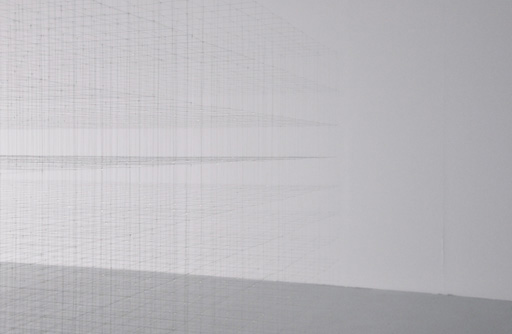

Now, my favourite Stella works are all about the parallel lines, in particular those making the shift from the precise and colourful to the imprecise and tonal. In these large-scale works, Stella imparts a depth to the space between the lines, which in turn gives the lines a quality of hovering, or buzzing in space. The lines are journeying tail-lights, rays conceived by squinting at the stars, or the strangely orderly formations on the inside of my eyelids. Whatever they are, in these works Stella masterfully moves us from the minimal to the spatial - a transition with architectural overtones.

This October, the Whitney will present the most comprehensive retrospective of his work yet. If only I could get there.

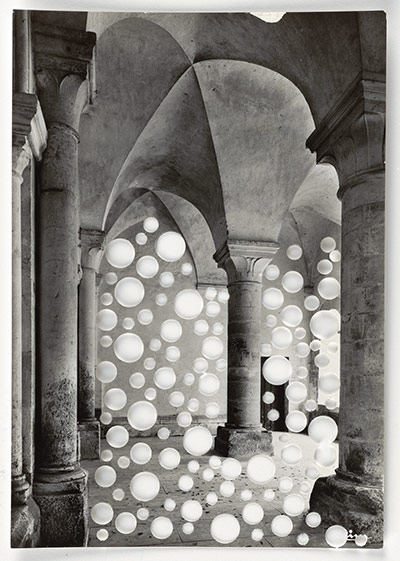

Ileana Sonnabend, 1963

Private collection

Zembesi, 1959.