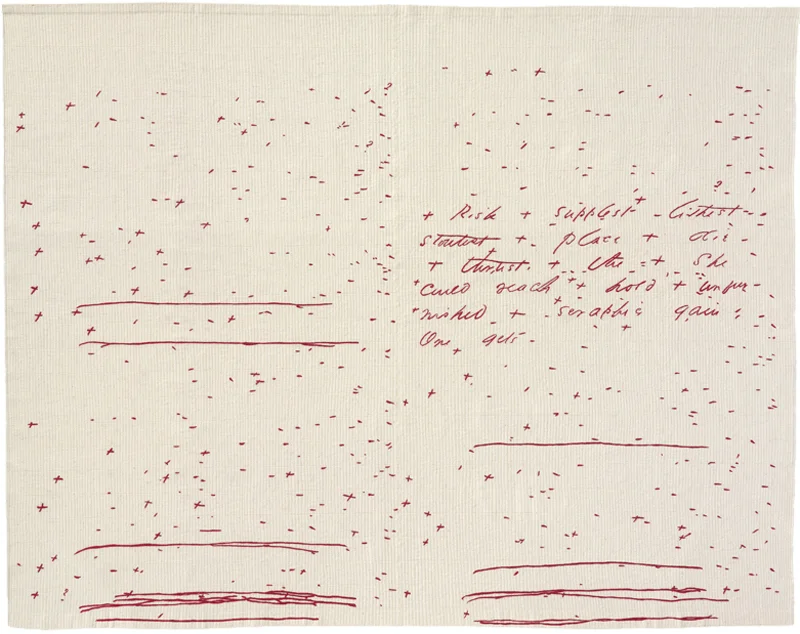

The Composite Marks of Fascicle 16. 6 feet high x 8 feet wide.

Cotton and silk thread on cotton batting backed with muslin.

More after break.

Between approximately 1858 and 1864, Dickinson grouped her poems into small handbound packets, later called fascicles. They are very humble bindings: stab-bound with twisted red and white thread and tied off teeteringly near the folded edge. The stitch held the stacked folded sheets together but made them a harder to open. The poems are composed on stationery typical of the nineteenth century, vertically folded sheets, plain, laid, or ruled paper with a small embossed image in the upper left corner. The packets contain eleven to twenty poems per grouping.

In 1981, Harvard University Press issued a landmark two-volume facsimile edition of Dickinson’s handwritten manuscripts, edited by R. W. Franklin. The edition includes forty of Dickinson’s fascicles—stab-bound packets (non-nested sheets of folded paper) containing eleven to twenty poems per fascicle. The manuscripts also contain a number of unbound sets; her late fragments and letters have yet to be published in facsimile editions. Dickinson’s own publication of her poems is highly specified given that she enclosed poems and lines from poems within letters in correspondence, tuning them subtly for different recipients.

Dickinson’s editorial legacy is complicated at best; her fascicles and fragments were dismembered, regrouped, scissored, and marked by her various editors as they changed hands and often her poems have been restructured and changed considerably for print. Even the current variorum edition of Dickinson’s work persists in defying her line breaks and removes or replaces her crosses with other marks (brackets and numbers to clarify, i.e. change, the system that Dickinson authored). By imposing conventional views of literary authorship (as expressed by book publication) and divorcing her poems from their formal integrity and its intended specificity, the implications of an unusual, complex, pervasive system are harder to understand.

I wanted to see what patterns formed when all of the marks in a single fascicle, Dickinson's grouping of poems, remained in position, isolated from the text, and were layered in one composite field of marks. The works I created were made proportionate to the scale of the original manuscripts but quite large—about 8' wide by 6' high—to convey the exact gesture of the individual marks. I scanned Dickinson’s manuscript facsimiles (about twenty pages per fascicle), edited them digitally to form composites of just the marks, and used a projector to transfer the marks onto cotton batting (to suggest a highly magnified page) prepared with a hand-sewn center line (a stand-in for the folio fold) and machine-sewn lines that replicated those of the light-ruled laid paper or blue-ruled paper. I embroidered Dickinson’s marks in with handspun hand-dyed red silk thread.

The fascicles from which I made composites showed clearly identifiable shifts in the size, gesture, frequency, and distribution of the marks. In contemplating such an odd physical study, one naturally forms one’s own questions about the nature and meaning of the marks; it makes their presence on the facsimile manuscript page more striking, systemic, factual—and their omission from typeset poems more evident.

I have never doubted Dickinson’s profound precision, however private, nor that the energetic relation of these marks and variants is anything but integral to her poetics. I have come to feel that specificity of the + and – marks in relation to Dickinson’s work are aligned with a larger gesture that her poems make as they exit and exceed the known world. They go vast with her poems. They risk, double, displace, fragment, unfix, and gesture to the furthest beyond—to loss, to the infinite, to “exstasy,” to extremity.

Fascicle sixteen contains the first insert page, a smaller sheet pinned in with a straight pin. The hand-embroidered black text is taken from from this insert page and reads: And could I further / “no”? Emily Dickinson wrote in a letter to Judge Otis Lord, “And don’t you know that “no” is the wildest word we consign to language?"