FAYLAND HOUSE

Slung over a sloped field of open ground poised to bloom with wildflowers, David Chipperfield’s Fayland House begins with a concern for context and history. Looking closely, however, the house transcends those qualities in search of a classic timelessness.

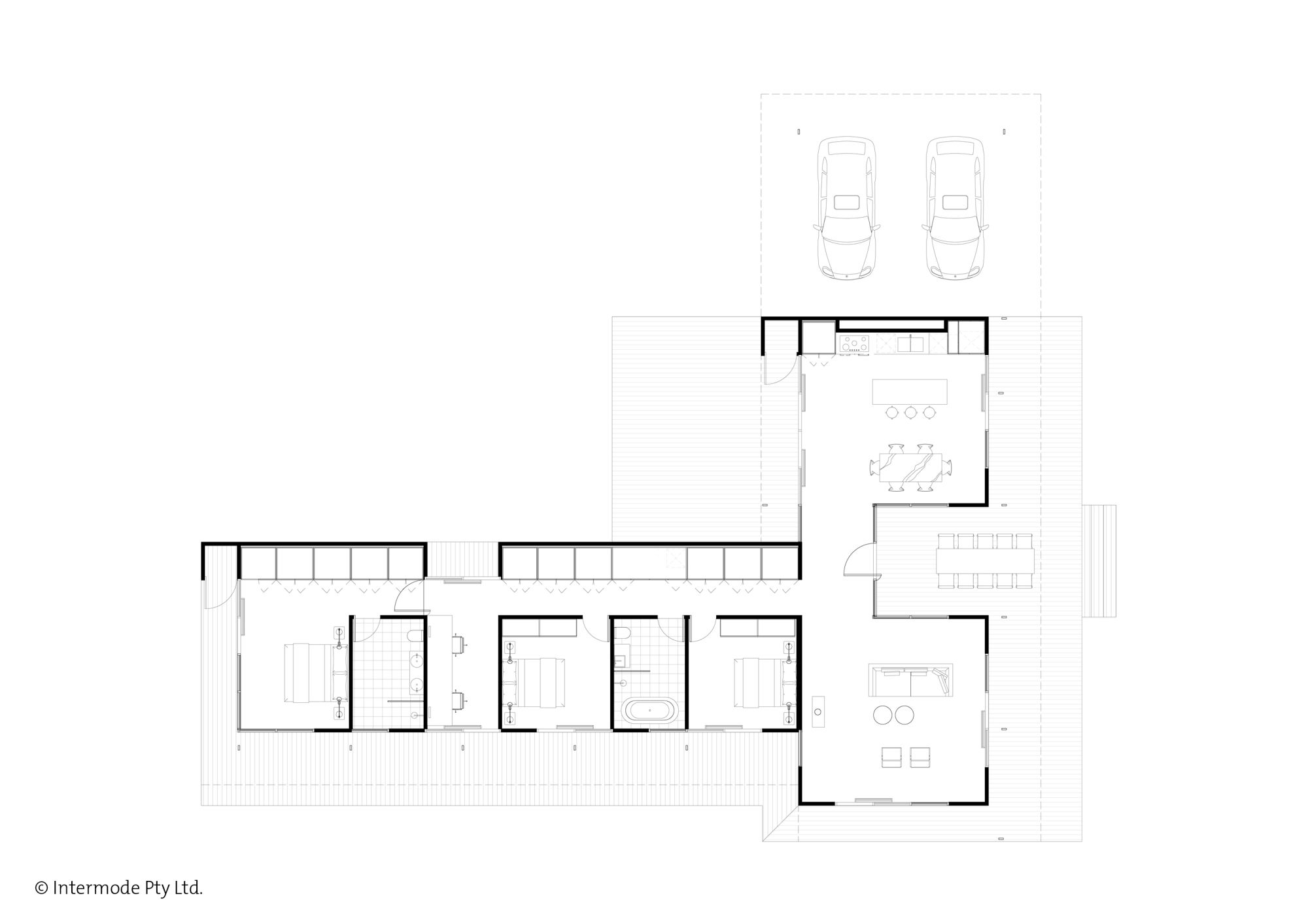

Living spaces languish alongside one another on the front, opening to the view, while ancillary spaces tucked behind rejoice in light from the courtyards. The resulting quiet interplay of interior space and varied landscapes is captured as the camera pans, silently through space in the film. The overlap of view and frame lends a quiet expansiveness to the project.

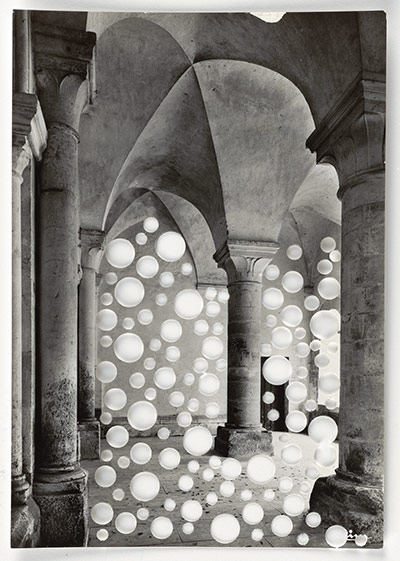

But it is the unmodulated run of circular columns along the front of the house which most intrigues us. The chalky, mortar-sponged white-brick is heavy and full and of the earth; with a generosity which extends the house outwards to the sky. Somehow regular and yet surprising, the columns express a classicism which is beyond perception. In an article in Architectural Review, Ellis Woodman perceptively suggested the effect of the columns is similar to the effects cultivated by the work of artist Donald Judd. He concluded his thoughts with a grace so deserved by the building that I cannot help but defer to him here:

“The abiding impression is therefore one of invitation to movement. It is a house where one lives on one’s feet and takes pleasure in the constantly shifting relationship to the landscape beyond. ”