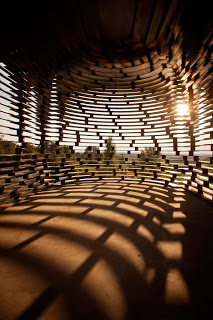

CELLO IN THE CHARRED CHAPEL

Sometimes you come across someone doing something that makes you sigh.

German-Korean musician Isang Enders' rendition of Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 within the sacred, charred interior of Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel is one of those moments you can't help but wish was quietly, selfishly your own.

It's been a long time since I list picked up a bow and drew it across the strings of my cello. Re-establishing my love for playing that deep, aching instrument has been on my list for quite a while now. But the things that make cellos so human - their size, weight, and equal parts fragility and strength, also make them cumbersome additions to the life of a 25-year old who rents her home and doesn't know where she may move to next.

So in the cello-less meantime, playing the piano in some of my most revered architectural spaces seems like a bucket list worth pursuing. The trick is just going to be getting myself, and the piano, there.

After that, those encompassing forever moments will come easy.